Emergency dollar liquidity for non-residents

30 March 2020

The covid-19 induced crisis has revealed the difficulties of the rest of the world to obtain liquidity in dollars when needed. Dollars are the most important monies and used extensively in international transactions. When dollars dry up there is a risk of severe financial disruptions. Non-residents are particularly affected amid the lack of an external contingency mechanisms. Siloed access has complicated distribution of dollars. The extension of the Federal Reserve swap lines may heighten the dollar liquidity divide.

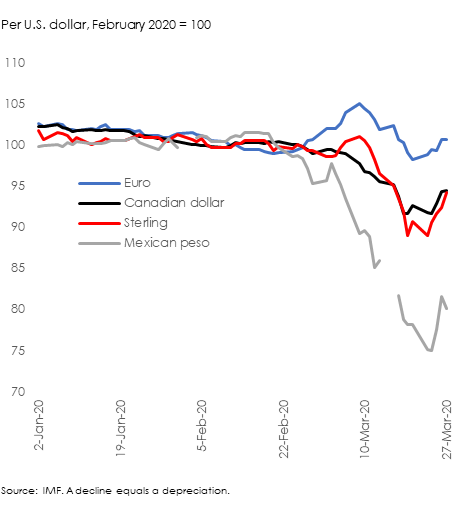

The sudden decline of dollar liquidity manifests itself in short-term exchange rate movements. Often in times of financial distress, there is flight to dollars. The foreign exchange market expresses shifts in the relative demand for monies. Since early-March, peak to trough, the euro has remained broadly flat against the dollar, sterling and the Canadian dollar depreciated by 11 percent and 8 percent and the Mexican peso by 25 percent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Exchange rates

Important differences exist between dollar liquidity for resident entities in the U.S. and non-residents entities. The Federal Reserve can provide near unlimited short-term liquidity to accommodate directly sudden demands from resident banks. It offers no such mechanism for non-residents.

Four mechanisms are available to offer emergency dollar liquidity to non-residents: Central bank foreign exchange reserves, Federal Reserve dollar liquidity swap lines, special drawing rights, gold and IMF loans. Some mechanisms are slow or complicated to mobilise. Most mechanisms are limited in the amount of liquidity support they provide.1 While evidence is mixed to what extent higher international liquidity produces lower exchange rate volatility, very low levels of international liquidity will have a considerable adverse effect on the exchange rate.

The first line of defence for many central banks are normally foreign exchange reserves. The Federal Reserve dollar liquidity swap lines have been expanded following the Lehman Brother crisis. Other sources of international liquidity are gold and SDRs. An IMF arrangement would be the last line. All arrangements except foreign exchange reserves and gold sales are conducted through central banks only and not banks.

Foreign exchange reserves are held typically in high quality fixed-income securities denominated principally in dollars. They normally represent the bulk of available international liquidity but differ significantly in proportion to economic activity, being a proxy for liquidity demand. Central banks have been reluctant to use foreign exchange reserves at a large scale as the level of reserves itself conveys market confidence. This “fear of intervening” limits the actual utility of reserves.

Other sources of international liquidity like SDRs or gold are difficult to mobilise. SDRs represent a relatively small proportion of international liquidity and are hardly used. Gold is complicated to sell in large quantities and only some European national central banks have remaining significant pools of gold reserves. The IMF flexible credit line provides unconditional financing but the limited resources of the IMF would prevent any large deployment to several countries at the same time.

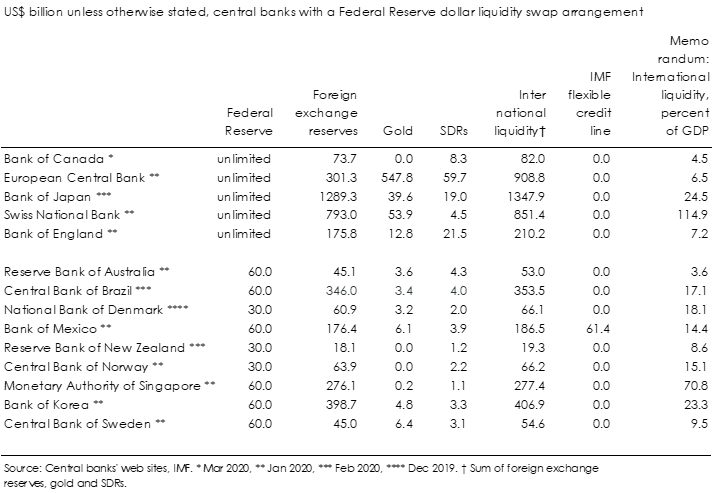

The Federal Reserve dollar liquidity swap lines have become a critical mechanism to offer emergency liquidity in dollars. The swap lines as part of the standing arrangements with the Bank of Canada, European Central Bank, Bank of England, Bank of Japan and Swiss National Bank are in theory unlimited though unlikely in practice. While it doubles access in foreign exchange for Australia, it represents merely one seventh of the international liquidity of the Bank of Korea (Table 1).

Table 1. Emergency liquidity

The distribution of international liquidity is highly uneven. There is no mechanism, except through the IMF and the Federal Reserve swap lines, to distribute liquidity more widely. Significant differences in liquidity access may also unduly build pressure on the weaker central banks. The highly unequal limits among parties to the Federal Reserve swap lines also risk exacerbating market perception that some countries will not be able to accommodate the most pressing demand for dollars dividing the international economy into dollar haves and have-nots.

The IMF has resources of about US$1,000 billion and a remaining capacity to lend of about US$800 billion (less than 1 percent of world GDP). Countries normally approach the IMF only when they have come under considerable pressure as, except in the case of IMF flexible credit lines, IMF lending involves substantial supporting economic and financial measures. The IMF provides in principle a mechanism by which countries make available excess liquidity to other countries and can accommodate through borrowing ad hoc additional liquidity supply. However, the borrowing from countries with considerable resources to supply liquidity has remained relatively modest. The U.S. provides US$38 billion under the New Arrangements to Borrow and US$113 billion in quota resources.2

Dollar liquidity remains essential for orderly international transactions. The present arrangements to obtain dollars in emergency situations remain incomplete and insufficient. While several countries have built considerable defences there is no structure to ensure an effective distribution of dollar liquidity across countries. The Federal Reserve swap lines are small except for the standing arrangements and available only to a very limited number of countries. The IMF resources are too few to offer bazooka-style support. Most external support is available to central banks only. Covid-19 serves as a reminder that the global financial safety net remains work in progress.

1 There are other arrangements including swap lines with the European Central Bank (ECB), Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM), People's Bank of China (PBoC), Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR) are disregarded.

2 The New Arrangements to Borrow is scheduled to double from January 2021.